"Before, we used to go to bed hungry and my mom couldn't buy us school books. But now we can afford both books and school uniforms," says eight-year-old Epakan Esekon.

The drought in northern Kenya is the worst in over 40 years. In Turkana district, one in three children is at risk of acute malnutrition. Epakan lives here with her parents and three siblings in the small village of Ngikwatex. Her family is used to droughts every year and has adapted their lives to the weather. But in recent years, climate change has made the dry spells longer and the consequences worse. Livestock die, crops fail and families go without food. Sometimes for days at a time.

Aloe vera cultivation was the solution

But amidst the cracked ground, something green has started to grow. For Epakan and her family, it was aloe vera that turned their lives around. When the family was at its worst, mother Aweet received support and training from Erikshjälpen that enabled her to start growing in the dry landscape. She learned which cultivation techniques work best, how to prepare the sap from the leaves and what it takes to sell successfully in the local market.

- I have been given many good tools to cope with all the challenges when the drought comes. Now I can feed my family two meals a day and the children can continue going to school," says Aweet.

Growing aloe vera may seem like a small change. But for Epakan it is actually life-changing. The money isn't just for food - now her mother Aweet can afford to send her children to school. And for the start of the school year, Epakan has been given a school uniform, shoes, socks and exercise books.

12-year-old Fatoumata had to build a new life in a refugee camp far from home. Her dream is to one day return home and work as a midwife.

- We had to leave everything. Our village, our school and our home. It happened so fast and I didn't get any of my things. No clothes, no toys, not even my birth certificate," says Fatoumata.

In Mali, the security crisis since 2012 has affected the lives of thousands of children. Fatoumata is one of them. When her school closed after terrorist attacks, her family chose to leave their home village in the hope of finding a safer life.

Life in the refugee camp

Fatoumata lives with her family in Ségou, in a refugee camp located in western Mali. Growing up in a refugee camp is tough.

- The whole family sleeps together in a small room. There is no place to be alone," says Fatoumata.

The lack of food means that many people can never eat enough. People are crowded into small spaces and the lack of sanitation and clean water means that diseases spread easily. Many feel very unwell and the risk of abuse is high.

Difficult to start a new school

In the midst of the unrest, Fatoumata was able to go back to school, but the first years at her new school were also particularly tough. At school, Fatoumata was bullied by other children. This made it difficult to focus on her school work.

- They teased me about my looks and called me names. I was always alone and I had no friends," she says.

When Erikshjälpen started a children's rights club at Fatoumata's school, things changed. In the club, the children learned more about inclusion and the right to education, health and safety. And Fatoumata has finally found new friends and regained her motivation for school work.

- The school works well. My classmates are nice to me now, even though I was excluded at the beginning.

The dream of a better future

Fatoumata is one of many children in Mali growing up with fear, hunger and insecurity. But thanks to the opportunity to stay in school, she has hope for a better future.

- It was difficult at the beginning but school work is going well now, which makes me happy. At the same time, I'm still afraid of many things... Afraid of being attacked by armed men and of being assaulted.

Although Fatoumata still fears the violence around her, she has a dream: to return to her village when peace comes and work as a midwife.

In Mali, more than 400,000 people are currently displaced within the country, many of them under the age of 18. They are fleeing because of unrest and hunger.

In 2024, more than 1,700 schools were closed due to the threat of terrorist attacks. This means that 520,000 children have lost their education and a safe place to be.

In the regions of Ségou, San and Koulikoro, Erikshjälpen works to strengthen children's rights by enabling education for refugee children. Here, children get access to, among other things:

- Temporary schools in refugee areas.

- Teaching via radio and digital media.

- Intensive training programs (Speed Schools).

- child rights clubs that strengthen community and self-esteem.

Supporting children's right to education

Help give more children the chance to go to school and dream of a bright future. Support our work for children's right to education and leisure.

Give a gift to children's right to education

Nancy Mbiti is the 18-year-old in Western Kenya who is calling for sanitary pads to be free for all girls and women in Kenya. She is one of several brave girls at her school who have started to speak out against an unequal society.

For us in Sweden, it may not be seen as a big problem. But for girls and women in Kenya - especially in rural and poorer areas - access to sanitary protection is not a given. And even if it is available, it is not certain that everyone can afford it.

Nancy talks about girls her own age who have been forced to use rags or other textiles as sanitary pads because they can't afford to buy pads at the store. Sure, sometimes sanitary pads are distributed at school, but the distribution is often unfair and can end up in the wrong hands.

- We want politicians, especially those in Parliament, to pass a law that provides free access to sanitary protection across the country. If it's free, it's not worthwhile for teachers, for example, to get hold of pads and then resell them. It would also mean that no more girls would have to sell sex to afford sanitary pads and that the number of teenage pregnancies would decreasesays Nancy.

Writing opinion pieces to influence

When Nancy was in fourth grade, she came into contact with Erikshjälpens work in Kenya and was able to continue going to school thanks to ourcollaboration with the local organization Kakenya's Dream. Last year she graduated from high school and now she dreams of getting into university and studying to become a teacher. Another dream is that the view of menstruation in society to change.

- Free sanitary pads should be available in all health centers so women and girls can pick up pads whenever they want. This should be be as normal as having condom machines everywhere," she says.

Every month, Nancy meets girls of the same age who are struggling to get hold of sanitary towelsand she realizes that it's a topic that no one really wants to talk about. Something she wants to change. So she tries to talk about Menstrual health with her classmates and write op-eds in local newspapers to bring about change.

- We cannot cannot be silent. People are a natural part of of life and something that we must dare to talk openly about. It is our right to have access to menstrual protection andand should not depend on whether you can afford it or not.

Consequence of menses

In May, Erikshjälpen draws attention to Menstrual health and girls' right to health and hope for the future. You can join us and make a difference!

Read more about Erikshjälpen's work for men's health.

To go to school. Not to be married off. To have the opportunity to dream and to dare to believe that the best is in the future. It is the right of every child.

Today, there are 250 million children around the world who cannot go to school. Jannatul Ferdus, 11, is one of the children at the Pakkhali Education Center, an education center supported by Erikshjälp's donors. We are in southern Bangladesh, out in the countryside where the landscape is constantly changing and children's access to education is limited.

In the area of the Pakkhali Education Center in southern Bangladesh, there are around 500 families. Many of the children come here to receive remedial education and participate in various activities. There is also a parent group attached to the center. Few children here continue their studies beyond grade 5, but at the center they are supported to cope with school and prepare for further studies. Last year, eight children were helped to progress to secondary school.

Currently, 33 students are enrolled at Pakkhali Education Center, of which 22 are girls, grades 2-5.

- We get extra lessons and help with homework. But we also get to dance and sing and have fun together," says Jannatul with a smile.

Poverty, poor roads, long distances to school, low levels of parental education and marriage are some of the reasons why many children do not attend school for many years. Families cannot afford to send their children to school. Instead, girls risk being married off and boys are forced to work. Many children have parents who did not go to school themselves and therefore do not receive much support with schoolwork from home. This is why the center is so important! Several children have been helped to apply for scholarships that enable them to continue studying despite their family's financial situation.

- Here we get the opportunity to prepare ourselves and we get help to pass school so that we can continue our studies," says Jannatul. She continues:

- We have different study circles and support each other. We also celebrate and recognize each other when things go well.

Inside the center, there are safe adults who support the children. Outside, the children grow vegetables, fruit and flowers. Together they have started a small fund, through which they help each other when someone in the group is having a particularly tough time financially.

Disaster preparedness, sustainability and equipping children to adapt to climate change is one of the objectives of the activity. Giving children a better understanding of their rights and being involved in influencing their local village is another. Giving children meaningful leisure time and the opportunity to succeed in their studies is a third. And the benefits are enormous. The children shine when they talk about what the center means to them, this is their context.

- We take care of each other and the center together, it's fun to be part of it, says Jannatul and her friends next to her nod eagerly.

Together with our local partner, Erikshjälpen supports several interventions in Bangladesh, to fulfill children's right to go to school, ensure that they feel good and feel safe.

Support our work for children's right to education

Thanks to you, more children can go to school and dream of a bright future.

Give a gift to children's right to education

What difference can a toilet make to girls and the work for girls' rights and a more equal world? For Shukhi and Piya and all their friends in Mongla, in southern Bangladesh - it makes all the difference. Thanks to the school's new toilet, girls' school attendance has increased. The girls can now also concentrate on their schoolwork in a whole new way, absorbing the knowledge and performing better at school.

It is not just the toilet itself that has made the difference. It is also the recognition that girls' needs, situation and challenges are real. It is the signal that girls are important. Yes, that they are and are seen as a resource and a force in society, and that they have the right to be given the conditions to educate themselves and help shape their own future.

- This toilet affects our everyday life and our future. Now we have the opportunity to keep up better with education and thus we have better conditions for the future, says 15-year-old Piya Mong, one of the students at ABC Secondary School in Mithakhali.

Lack of protection has been a problem

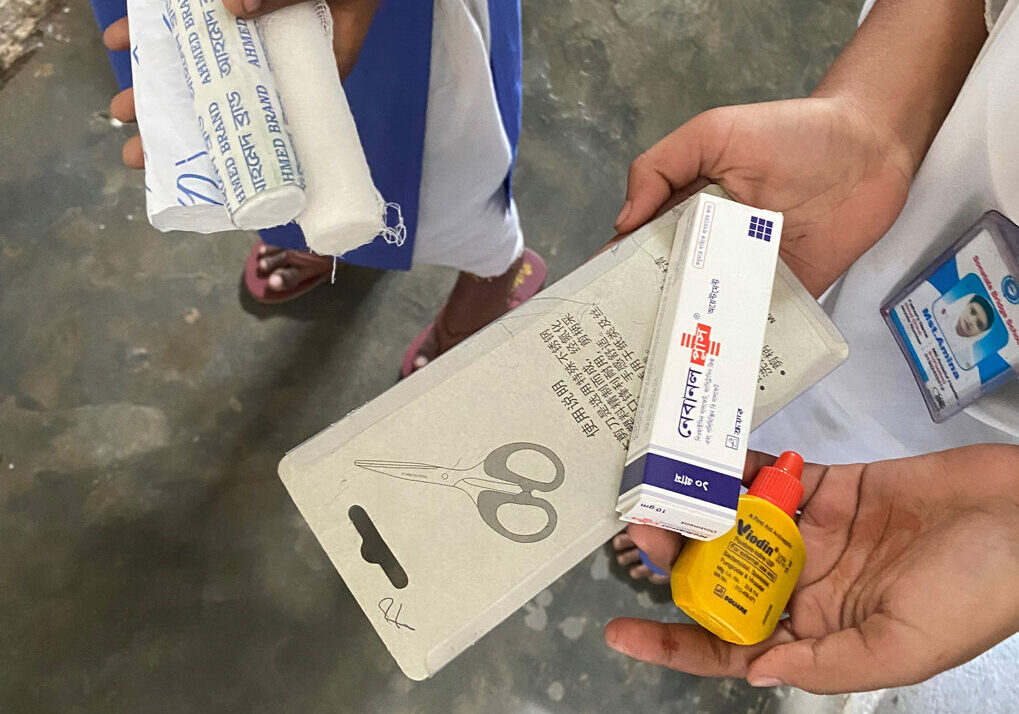

The school has around 250 students in grades five to eight. Piya and his friend Shukhi Mony, 12, show off the school's new accessible toilet. It houses both a traditional toilet with a hole in the floor and a water toilet, the first in the area. There are also several new sinks and a cupboard full of everything a girl might need during her period.

- "When we haven't had access to sanitary towels, we've used clothes and other textiles as protection, but it's not very good because it's so unhygienic. The water we wash ourselves and our clothes in is not very clean either, and there are many risks of disease," says Piya.

Join us in supporting our work for children's right to health

Thanks to you, more girls can have access to safe Menstrual health and thus have a greater opportunity to reach their full potential.

Swisha a gift

900 92 83School - a safe place

The girls' math teacher, Selina Akter, confirms that the toilet means a lot. The girls now feel much safer and their school attendance and results have improved significantly.

- In the past, when the girls had their periods, they avoided coming to school. Now they have access to everything they need to feel safe and hygienic here at school, and they miss less classes," she says.

Previously, all the school's students had to share two worn and very dirty toilets. The walls of which are not sealed, through gaps you could peek in even though the door was closed.

- The old toilet was so dirty, you didn't feel safe there," says Shukhi.

- "Yes, and there was always a queue, and since we didn't want to use them, we preferred to go home if we needed to go to the toilet. But because of the road, we rarely came back," says Piya. She adds:

- It feels great that we have a new toilet! It's so clean here, no dirt. There is running water and sanitary pads.

Fewer interruptions in schooling

Piya and Shukhi have a couple of kilometers to go to school and the road can be very busy. Despite this being the case for most of the school, they and many others usually chose to walk home to go to the toilet. Despite the fact that they would then miss classes, which clearly affected the results.

- The girls really didn't want to use the old toilets. Some of them avoided drinking water the whole school day so they wouldn't have to go," says Selina Akter. She continues:

- "It also took a lot out of the girls' concentration to keep thinking about how to avoid the toilet. They were unfocused but didn't want to talk about it either.

- Yes, now we are much more present in school than before. It feels safe and it feels fun to be here. We no longer miss so much of the school lessons," says Piya.

Millions of girls are affected and have it every month. Menstruation. Yet we rarely talk about it. In parts of the world, girls are forced to stay home from school during menstruation, missing out on much of their education. At Shonatola Bridge School in southern Bangladesh, there are separate toilets for girls and boys. The girls' toilets include sanitary pads, tampons, washcloths and painkillers that enable girls to go to school, even during their periods.

The Shonatola Bridge School in southern Bangladesh is bustling with life. Lessons follow one another. First math, then language, then sports. And then the science club and the girls' group. When the bell rings, it's break time. Sabona and Amina are best friends and are in year seven. They say this school is different from other schools in Bangladesh in many ways.

-"The school means safety for me. Here I have learned to speak in front of people and here there is clean water and clean toilets," says Sabona Akter, who is 15 years old.

Because her family could not afford it, she was forced to drop out of school after grade five. She was at home for two years before, after this school was built, she was able to start again.

- "If I hadn't gotten a place at this school, I would have had a completely different life. I would have been married off or forced to take a job at the textile factory to help support my family," says Sabona.

Only school in the area

Two cohorts of students are currently attending Shonatola Bridge School in southern Bangladesh. The school is the only one in the area for children in grades six to eight. It is located in a rural area with difficult access. Thanks to solar panels, the school has electricity and internet access, allowing the children to benefit from both digital and classroom-based education. There are separate toilets for girls and boys and access to clean drinking water. Many of the children attending the school live in extreme poverty and would not be able to continue their studies if it were not for the school. Many of them have previously been forced to drop out of school.

Join us in supporting our work for children's right to health

Thanks to you, more girls can have access to safe Menstrual health and thus have a greater opportunity to reach their full potential.

Swisha a gift

900 92 83Being a girl in Bangladesh

14-year-old Amina Akther is also happy to have the opportunity to continue her studies. She talks about what it is like to be a girl in Bangladesh. "Many have a long and dangerous journey to school. And that there are risks of assault and abuse that mean that girls should not go out alone. Many girls also risk being married off. And then there is menstruation, which causes many girls to miss large parts of their schooling.

- "Many children here stay at home during their periods and miss a lot of school," she says.

Girls can now come to school even during their period

At school, girls receive a lot of support, which they do not take for granted based on previous experiences.

- There is a separate toilet just for girls, with pads and everything you need, it feels safe. We girls can come to school even when we have our periods, the school helps and supports us," says Amina and continues:

- In school we learn about sanitation and hygiene. About washing our hands properly and taking care of ourselves. My mom is very happy about the opportunities I have now, she has not had those opportunities.

In Rampal, in southern Bangladesh, is the Surjer alo Child center, supported by Erikshjälpen's donors. The center is a kind of recreational activity, with children's clubs and other activities for the children in the area. There, the children learn about children's rights and practice putting their feelings into words, expressing their opinions and being involved in influencing their situation.

At the Surjer alo Child center in southern Bangladesh, 16-year-old Ayesha Akter and 15-year-old Preema Das participate in the children's club activities. Here they have learned about children's rights and practiced expressing their feelings, needs and opinions. 16-year-old Ayesha tells us:

- Before, I couldn't talk to my parents at all, but it's better now. Now they hear me and my opinion matters, that makes me happy.

Her friend Preema Das, 15, fills in:

- I used to be shy and no one in my family knew what was going on or what I was going through. I often felt overlooked, especially when my brothers got more attention than me. It's better now but it's still very unequal.

Lack of sanitary protection and clean toilets has been a problem

The girls are almost finished with secondary school and both dream of studying further. Keeping up with school has been tough. They both go to a government school and the lack of sanitary pads and clean toilets has been a problem ever since they started menstruating. Preema tells us:

- In the past, we and our mothers used clothes as protection.

- Yes, there were. There weren't always pads or other protection, so we used clothes, but it was unhygienic in many ways. Now we can buy sanitary pads through the center for half the price, which makes it easier," says Ayesha.

Join us in supporting our work for children's right to health

Thanks to you, more girls can have access to safe Menstrual health and thus have a greater opportunity to reach their full potential.

Swisha a gift

900 92 83Missing school due to menstruation

Both girls say that they have missed quite a lot of school due to being at home during periods of menstruation.

- I used to stay at home for the whole period, but now I usually only stay at home for the first two or three days.

- To avoid missing too much, we try to study at home, but it's clear that people have made it harder to keep up," says Preema.

They dream of changing

They talk about life as a girl in Bangladesh, about everyday life and that they feel that although girls and boys should have the same rights, boys are often given priority.

- "Boys are more important in the family and they are always given priority in society and in school," says Preema.

- "Girls don't have the same rights as boys in practice," says Ayesha, citing an example of a particular dish in Bangladesh, where the head of the fig is considered the tastiest part. She continues:

- "My brother is always asked if he wants the fish head, I don't want the fish head but I would like to be asked," explains Ayesha.

Despite the challenges they face, the girls have clear goals. They want to work for the betterment of society and they want to be involved in changing their situation and that of others.

- Soon I will have a higher education than my brother. My mother supports me, she never got to study herself, so she wants me to have this opportunity," says Preema.

Alice, 13, fled Ukraine with only the bare essentials in a backpack. Alice and more than 43 million other children around the world are today fleeing war and unrest.

When Russia invaded Ukraine, Alice's life went from safety to danger in a matter of hours. She saw her home and her entire childhood town destroyed in a few days of intense fighting.

Alice is 13 years old and comes from the town of Hostomel, located a few miles northwest of the Ukrainian capital Kiev. Hostomel was subjected to air strikes, shelling and heavy ground fighting that left homes, schools and shops in ruins. Even running water, electricity and heating disappeared. All that was left was destruction and fear.

- Our house was damaged. All the windows were destroyed and almost everything we owned is gone. Now I only have a cell phone, but it's hard to do schoolwork on it," she says.

After nine days in a shelter, Alice, her older brother and their mother managed to escape the city. Alice only had a backpack with the bare essentials. A pillow, an extra pair of shoes and a cell phone charger.

Give your Christmas gift to Alice and other refugee children!

Alice, her brother and their friends have been helped by participating in psychosocial activities, but the anxiety is still there.

Give a Christmas gift

900 92 83The nightmares have disappeared. Instead, 14-year-old Djemirata can dream of training as a seamstress and one day reuniting with her family in her home village of Goinlingin.

In Burkina Faso, around two million people live as internally displaced persons. The country has been politically unstable for years and was hit by two military coups in 2022. This led to a dramatic increase in violence and now an estimated 4.9 million people are in urgent need of Humanitarian Assistance.

For 14-year-old Djemirata Nabalum, violence came very close. Her village was attacked by armed terrorists and she was forced to flee to the town of Kaya in central Burkina Faso. The security situation in Kaya is somewhat better than in the rest of the country and just outside the town is the Tansega Wayalguin IDP camp.

In the refugee camp, Erikshjälpen works together with the local partner organization Organisation Catholique pour le Développment et la Solidarité, OCADES, to support children and families who have fled from armed militias that terrorize large parts of the country.

- We are well looked after and get to take part in fun leisure activities that make us feel good here," she says.

Give your Christmas gift to Djemirata and other refugee children!

Helping more refugee children to live in safety.

Swisha a Christmas gift

900 92 83Children's nightmares have disappeared

There is a strong focus on psychosocial work. For example, many of the children in the refugee camp have seen their parents or other adults killed. Together with UNICEF, OCADES and Erikshjälpen run a special activity area, Children's Friendly Space, where children can feel safe and at the same time have access to education and leisure activities.

- Our nightmares disappeared when we started hanging out in the Children's Friendly Space. Now we dream about playing together instead. We are very grateful for that. The whole environment makes me feel more secure," says Djemirata.

Since arriving in Tansega Wayalguin refugee camp, Djemirata has begun to dream of a future as a seamstress - and, of course, of one day moving back home and reuniting with her family.

- When I look ahead five years, I see myself learning to sew and making a living as a seamstress. I also want to pass it on to my future children, just like my mother did, so they can be self-sufficient in the future.

Halidou has met new friends

Around 120,000 people live as internally displaced persons (IDPs) in the city of Kaya, and over 77,000 of them are children under the age of 17. For 15-year-old Halidou Sawadogo, who has fled to the Tansega Wayalguin IDP camp with his family, every morning starts with a visit to the Children's Friendly Space.

In the evenings, he works in the fields to help support his family.

- I have met many new friends at Children's Fiendly Space and we have a lot of fun hanging out together. Despite all the challenges, I try to find the joy in the small things. Children's Friendly Space has meant a lot to me, because I have something to do during the day instead of just thinking about everything that is difficult," he says.

The world's most forgotten conflict

The NRC Refugee Council ranks the situation in Burkina Faso as the world's most forgotten conflict in terms of media coverage, aid and the international community's willingness to resolve the conflict. Meanwhile, the Global Terrorism Index 2023 ranks Burkina Faso second among countries most affected by terrorism - just behind Afghanistan.

Thanks to Erikshjälpen's work in Burkina Faso, more children can feel safe in one of the world's most insecure countries.

Author: Johan Larsson

For 14-year-old Viktoria, Russia's war of invasion against Ukraine turned her life upside down. But with the help of Erikshjälpen, Viktoria can dream of one day being able to return home again.

For the past year, 14-year-old Viktoria has been living with her mother, father and older sister in a one-room modular house in the Ukrainian city of Irpin. Before the war, the family lived in an apartment in Irpin, but everything changed one morning at the end of February 2022 when the family was woken up by loud explosions after Russia started its war against Ukraine and fierce fighting broke out in Irpin.

- It was very scary. We rushed to a shelter where we spent a day and a night," says Viktoria.

The next day, the family was evacuated from the city. All but the father then made their way to Poland.

- My father couldn't come with me. "All men under the age of 60 must stay in Ukraine to defend the country," explains Viktoria.

In early April, the Russian army withdrew from Irpin and Viktoria's family decided to return. They didn't want to stay in Poland because Ukraine is their homeland where they want to live. Before they returned, Viktoria knew that her family's house had been destroyed in a Russian attack.

- But when I returned here and saw it with my own eyes, I felt terrible. It was destroyed and black with soot. I was very sad," says Viktoria.

Support from Erikshjälp's partner organization

Initially, the family stayed with relatives in Irpin, but in the fall of 2022 they moved into the room in the modular house that is now their home. The room is 13 square meters and the family shares a bathroom, toilet and kitchen with other IDPs.

- Our living conditions are completely different from how we lived before, but I've gotten used to it. Now it feels okay," says Viktoria.

She goes to school in Irpin and in her spare time she mostly hangs out with friends. Sometimes life gets boring, but on this day Erikshjälpen's Ukrainian partner organization WCU has been visiting and had social activities. Viktoria has participated in them with some other children and young people. During the activities, the children get the opportunity to process traumatic experiences while having a fun time.

- I love it when volunteer organizations come here and do activities with us or give us presents. For Christmas and New Year last year, we had to write Christmas wish lists. I wished for, and received, a power bank that I often use here," says Viktoria.

Give your Christmas gift to Victoria and other refugee children!

Helping more refugee children to live in safety.

Swisha a Christmas gift

900 92 83Dreaming of lasting peace

Electricity is often lost in the 'modular city' because many power plants have been destroyed in bombings. The Russian army often fires missiles at Irpin, but the Ukrainian air force manages to destroy most of them in the air.

- The airplane alarm sounds quite often and then we have to run to the shelter. It's scary, but we've had to get used to it," says Viktoria.

Victoria usually reads or draws when she is scared. As an adult, she wants to be an artist.

- Now my greatest wish is for our house to be renovated so that we can move back home. I don't know when that will happen. It might take five years," she says.

Victoria believes, and hopes, that Ukraine will win the war and that there will be a lasting peace.

- Even though there is still a war going on, I have high hopes for a better future," concludes Viktoria.

A humanitarian crisis in Ukraine

Since Russia's invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022, UNHCR estimates that 6.3 million Ukrainians have fled abroad and more than 5 million are living as internally displaced persons. In addition to the large number of refugees, UNHCR estimates that over 17 million people are in urgent need of Humanitarian Assistance.

Author: Bengt Sigvardsson