She was just five years old when her family sought refuge from the civil war in the jungle. Today, Maran Hkawn Nu has been living in a refugee camp in Myanmar for 12 years.

The family left everything behind, their home, their daily life and all their belongings. First, the family took shelter in the jungle and then fled to the Shwezet IDP Camp in Kachin State, northern Myanmar. At the time, Maran Hkawn Nu was just five years old.

That was 12 years ago and Maran still lives in the refugee camp with her family.

- There are nine of us in the family so it's a big family. My mom looks after my brothers while my dad tries to find work to support the family. My sister and two of my brothers have disabilities and my sister still needs medical treatment," says Maran.

The family comes from Kachin State in northern Myanmar. There, an armed conflict between the Kachin Independent Organization and the Myanmar government has been ongoing since the military took power in 1962. After a 17-year hiatus, the conflict flared up again in 2011.

Give your Christmas gift to Maran and other refugee children!

Helping more refugee children to live in safety.

Swisha a Christmas gift

900 92 83Difficult to start over in the refugee camp

In Myanmar, there were hopes for a democratization process after the free elections in 2015, but after a coup d'état in early 2021, the military took power again. Conflicts increased throughout Myanmar and today around 1.5 million people live as internally displaced persons in the country.

For Maran and her family, starting a completely new life in the camp was a difficult adjustment.

- We have had to struggle very hard in the refugee camp. In the beginning, we had to cook, eat and sleep in a very small space. As I have three siblings with disabilities, I think we are the family that has suffered the most. Sometimes the other children in the camp tease my siblings and I can get very angry, even though I try to stay calm," says Maran.

Fighting for their siblings' schooling

In the refugee camp, Erikshjälpen has worked together with the local partner organization Kachin Baptist Convention to give the children a safe and secure life in the midst of the burning civil war. After decades of conflict, Myanmar is today one of the most insecure countries in Southeast Asia and, as always in armed conflicts, it is the children who suffer the most.

These range from high child mortality rates due to lack of health care to large numbers of children dropping out of education after primary school. In the Shwezet refugee camp, Maran struggles to keep her siblings going to school every day.

- I understand that my siblings are a bit behind in school because of their disabilities and I pray that they will do well. Even though we live in a refugee camp, I want them to succeed in their education," says Maran.

Wants to return home as soon as possible

Violence, drugs, trafficking, child labor and landmines are commonplace for many children in Myanmar. According to the Kachin Baptist Convention, many children live in constant fear of losing a relative or being killed themselves. The Kachin Baptist Convention works on the basis of a special child protection program where the children themselves are involved in activities that strengthen their protection against violence and various forms of exploitation.

For example, protecting children from being sexually exploited and helping those who have been exploited, or offering child soldiers the opportunity to start vocational training instead.

Maran dreams of one day being able to train as a nurse, but it is difficult. She has to help out in the family by taking care of her siblings, and she also has to do extra work in a laundry to earn money for her sister's treatments.

- We have now lived here in the refugee camp for twelve years. I wish for nothing but peace so that we can return to our home village.

Thanks to Erikshjälpen's work in Myanmar, Maran and her younger siblings can grow up in protection from the dangers of war.

Military coup forced millions to flee

In February 2021, the military staged a coup d'état in Myanmar and a state of emergency has been in place throughout the country since then. The military coup led to widespread protests and armed resistance against the military junta is ongoing throughout the country. In addition to a large number of deaths, the conflict has displaced over 1.5 million people.

Author: Johan Larsson

In Bangladesh, it is a national problem that many people do not have access to sanitary toilets. Through a children's club, which Erikshjälpen supports, they have gained better knowledge of personal hygiene, which has contributed to better health.

She is called a "hygiene hero"

Afsana Khatun is 13 years old and lives in an area called Pargobindopur Abashon in Bangladesh. In the community, Afsana has been given the title of "hygiene hero". Through the children's club that Erikshjälpen supports, she has learned about personal hygiene. Afsana now teaches her knowledge to family and friends, which has led to improved health for everyone around her.

Diseases spread easily

Apart from the fact that few people in the country have access to sanitary toilets, there is also a lack of understanding about how to dispose of waste safely. As a result, diseases are spread through contaminated waterways where garbage is dumped, and despite government interventions , progress is too slow. That is why it is important that children, like Afsana, become advocates for good hygiene.

At the kids' club, they talk about the importance of washing often with soap and brushing your teeth every day. They have also talked about small things you can do in everyday life to keep things clean around you. For example, wearing different slippers in the toilet than the ones you wear at home.

Fewer people get sick

It is Afsana's persistence and knowledge that means those in the village are now seeing an improvement with fewer people falling ill. All thanks to her teaching people about the importance of good hygiene.

Your contribution creates heroes like Afsana!

Author: Anton Eriksson

Around the world, girls receive little or no education. That's why Erikshjälpen is highlighting the important work being done in collaboration with the Postcode Lottery to improve girls' opportunities.

October 11 is International Day of the Girl Child. On this day, like all other days, Erikshjälpen wants to draw attention to the situation of girls in the world and emphasize the power of education as a tool for change. Today, more than 600 million girls receive little or no education. There are many reasons why girls around the world are forced to drop out of school, but poverty is often a root cause.

Girls are missing out on education

- For girls, it can also mean that they are married off very young, so that the family does not have to support them. The girl's value lies in being a virgin, and the younger she is, the more likely she is to be a virgin," says Marianne Stattin-Lundin, program advisor at Erikshjälpen.

Forcing girls to drop out of school may also be related to the environment in and around school. The route to school can be long and unsafe, with the risk of being subjected to various forms of abuse. Many girls also miss part of their schooling because they stay home during periods.

- "Menstruation is often a problem because sanitation at school is poor and girls feel uncomfortable, causing them to stay at home," says Marianne Stattin-Lundin.

Keya is now back in school

Keya, a 14-year-old from Bangladesh, was forced to drop out of school when her father passed away. Instead of going to school, she had to take responsibility for the household and her younger siblings while their mother was at work. The school she attended was far away, the road to it was unsafe and once at the school, teachers used violence against students when they thought they were talking too much. Keya's dream has always been to become a doctor and now she dares to dream about it again.

With the support of the Postcode Lottery and Erikshjälpen's donors, a new school has been built just five minutes from Keya's home. There, the teachers are supportive and Keya and her friends have the opportunity every day to continue to be curious and deepen their studies. At the school, students are challenged to engage with children's rights in various activities. The school has separate toilets to ensure that girls feel safe at school even when they are menstruating. The girls have also been given access to sanitary pads.

Suraeya escaped being married off

According to the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), one in five girls in the world is at risk of being married off. 17-year-old Suraeya, also from Bangladesh, escaped child marriage thanks to the knowledge and courage to stand up for her rights. Through the meetings at the children's center that Erikshjälpen supports, she has learned more about her rights. There, together with her friends, she has also learned and practiced how to raise their voices and express their opinions. There they have understood that they have the right to participate and influence their future.

Supporting work for girls' rights

Suraeya was brave and had many people supporting her. Her sister, on the other hand, was married off at the age of 13. Now Suraeya has only one year left in the local school, her dream is to become a fashion designer.

You can support the work for girls' rights by making a donation. Contribute to Erikshjälpen's work here:

Give a gift to education and leisure

Postcode lottery initiative for girls' right to education

You can also read more about the situation of girls in the world and the Swedish Postcode Lottery's initiative for girls' right to education, of which Erikshjälpen is a part, here

We are in a global education crisis

Postkodlotteriet – flickors utbildning

Thank you to those who support Erikshjälpen's work and to those who, through lottery purchases, help to improve the situation of girls. You are helping to ensure that children like Keya and Suraeya get an education and can dream of a better future.

Author: Frida Vingren

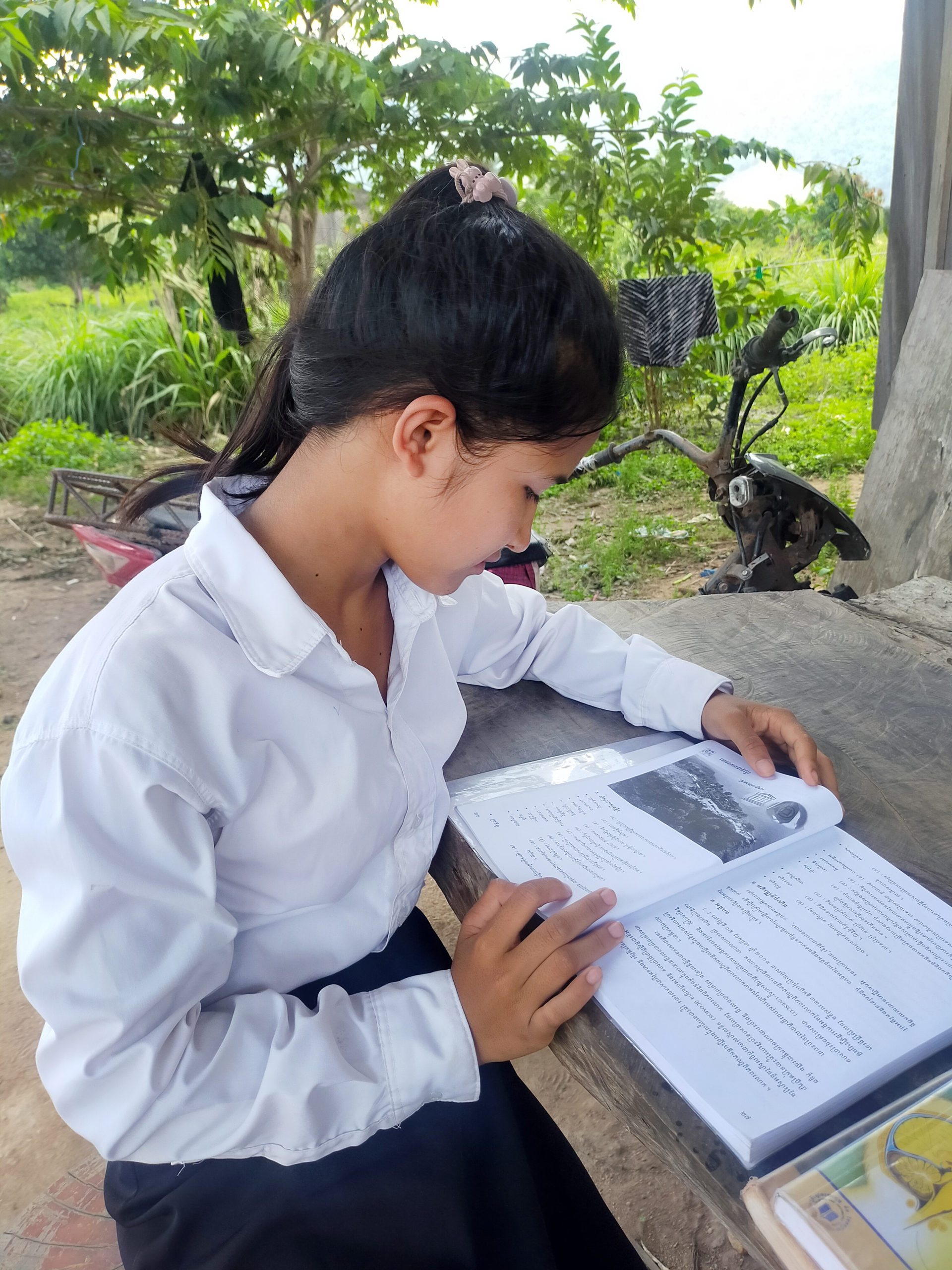

In Phnom Penh City in Cambodia, Erikshjälpen works together with the local Sunshine Cambodia Organization to strengthen children's rights and give them the opportunity to grow up in a world without violence.

Every child has the right to grow up in a world without violence. But in Cambodia, this is far from reality. In particularly vulnerable areas, it's not uncommon for everyday life to be marked by violence and abuse, both at home and in schools, and it's often adults - parents, older siblings or teachers - who use violence against children.

There are several reasons for what drives violence and therefore the problem must be addressed in as many ways. Together with our local partner Sunshine, Erikshjälpen works with targeted interventions that all, in different ways, aim to promote children's rights.

A large part of the work involves communicating knowledge about children's rights to all the adults around them. It is also about working with different social actors to strengthen children's safety in the public environment and to increase their opportunities to go to school. interventions that in the long term build children's self-confidence and give them a safer growing environment.

Much effort has been made over the years to promote children's rights in Cambodia, but there is still much work to be done. Especially when it comes to engaging and including the child's voice in decisions at different levels of society. Thanks to Erikshjälpen and Sunshine, girls and boys are supported in schools, youth centers and children's clubs to understand their rights - and to make their voices heard.

"Now I dare to tell my mom if I have any problems"

The beatings could come if he hadn't done his homework. Or if he was too tired to help at home. But now, 13-year-old Sereyvat and his mother have a warm relationship based on mutual respect between each other.

Sereyvat's childhood outside Phnom Penh City was long characterized by beatings and scolding. His mother Sokuntheary, who is widowed and infected with HIV, often took her bad temper out on her children, and Sereyvat would be beaten if he wasn't at school.

- Now she has stopped hitting and scolding me, instead she uses nice words and encourages me to do my homework," says Sereyvat.

Since 2017, the family has participated in family support activities and parenting clubs run by Erikshjälpen's local partner Sunshine just outside Phnom Penh City. Here, Sokuntheary has not only received support in her role as a parent or start-up capital to run a small food business, but also knowledge about how her children are affected by a childhood characterized by violence. Something that has paid off.

- Now I dare to tell my mom about my problems and she helps me solve them. There is also a big difference in how I behave myself and I notice that I have become more patient. Before, I often used to fight with other children at school, but now I don't do that anymore," says Sereyvat.

The support of Sunshine and Erikshjälpen has also given Sereyvat the courage to tell his mother if she hits him again, and he now knows his right to grow up in a world without violence.

- My teachers motivate me to come to school regularly. Whenever I have any problem with other students, the principal tells me not to fight with them. He also encourages me to study and tells me to think about my mother who is trying to earn money for my education and future," he says.

Example of costs

- 82 SEK - Annual cost for a parent to participate in the parents' club.

- 124 SEK - Excursion for a child with the aim of strengthening the child's self-esteem.

- 3100 SEK - Start-up capital for small businesses.

Video om Sereyvat och hans mamma

Before, 15-year-old Soeum didn't want to talk much about her period. She found it embarrassing and didn't really know what was happening in her body. Thanks to Erikshjälpen's work in Cambodia, she now has no problem asking for help - or going to school during her period.

School means everything to 15-year-old Soeum Sreynoch in the small village of Chrey Thom in north-western Cambodia. Here she gets to study her favorite subject biology, here she meets all her friends and here she meets her fantastic teachers every day. Her dream is to one day become a teacher herself and contribute to a safe upbringing for the local children.

But not all girls in Cambodia have the same opportunities as Soeum.

Especially in the remote villages of northwestern Cambodia, where knowledge of girls' personal hygiene is low, access to menstrual protection is poor, and schools often lack safe environments for students to maintain good Menstrual health.

All this means that many girls stay home from school - or at worst, drop out early.

- We were completely misinformed about menstruation before and there were many rumors spread among friends and the elderly in the village. That it hurts a lot, that it's dangerous and that it's shameful to talk about. But now we have been educated in school about personal hygiene and how the body works during menstruation," says Soeum.

We were completely misinformed about menstruation before and there were many rumors spread among friends and the elderly in the village. That it hurts a lot, that it's dangerous and that it's shameful to talk about. But now we have been educated in school about personal hygiene and how the body works during menstruation," says Soeum.

Here in northwestern Cambodia, Erikshjälpen is working with the local organization Hagar to increase knowledge about Menstrual health among the inhabitants of the small villages. The work has been very beneficial and has contributed to the replacement of old habits and traditions with new knowledge and greater openness about girls' personal hygiene.

- I want to see a change. This is a problem that hinders girls' access to education and safety," says Soeum.

The menstrual practices that used to exist in Soeum village were often painful and directly harmful to the girls. Like going down to the nearby river to wash and minimizing the pain with the cold water.

Now there is a completely different knowledge in the village about the importance of a good environment with access to clean water, soap and safe toilets. This ultimately means that more girls want to go to school even when they are menstruating.

- Sometimes I don't feel very well when my period comes at school. I can get stomach aches, have a bad mood and can be rude to my friends. But everything can also be just as normal. At least I've never had to stay home because of my period," says Soeum.

In residential areas where Erikshjälpen Framtidsverkstad is located, many children and young people feel that there is a negative image of their area and those who live there. They want to change that. The Future Workshops have become a platform where young people can make their voices heard. But also a place for their own interests and dreams.

Homework help is a popular activity that Erikshjälens Framtidsverkstad in the residential area Ekön in Motala organizes together with the football club Dribbla United. One of those who helps the children with their homework is sixteen-year-old Nassir Ali. Although Nassir has never received help with his homework himself, he would like to give this opportunity to the younger pupils in the area.

- I see myself in the children," he says. When the homework is done, the children have a coffee break to replenish their energy before the football training begins. For those who don't want to play football, other activities are organized.

Ekön is a multicultural area where many children live. It is also the only area in Motala where there is no recreation center. By offering children and young people free activities, homework help and discussion groups, Framtids- verkstaden is helping to even out growing-up conditions in Motala, while giving more young people meaningful leisure time.

- "I wish Erikshjälpen's Future Workshop had existed when I was younger. Then I would have had something to do and it would have been easier for my mom, says Nassir.

In Erikshjälpen's Future Workshops, faith in the future and community are created. Children and young people are given a safe place to express themselves and develop. This allows the young people to realize their full potential, while reclaiming the narrative of their hometowns.

Gränby is located just north of central Uppsala. It is one of the areas described in the media as an "exclusion area". There are certainly social challenges in the area, but Sudi Osman doesn't buy the description that Gränby is unsafe.

- A lot has changed for the better in Gränby since 2019. People have looked badly at our area, but those who live here are working to make it better. You shouldn't have to feel worried in Gränby," says Sudi.

Sudi is now 17 years old and came into contact with Erikshjälpen's Future Workshop for the first time in the spring of 2022. She was offered to work in the Future Workshop during the sports holidays and at first thought it could be a good first job and some extra money in her wallet. But once there, she found a place that was more of a context than a job.

-"All of us who meet here become like friends. We can both have fun at activities together but also talk about important things. The Future Workshop has become like my second home," says Sudi.

When you talk to Sudi, you quickly realize that she is a girl with skin on her nose who is passionate about Gränby and the young people who live there. Her commitment and voice took her to Almedalen 2022 where she participated in a panel discussion on young people's growing up conditions in Sweden organized by Erikshjälpen.

Now Sudi can be recognized in Gränby as "You from the Future Workshop!" and it's a role she enjoys.

-"When young people see that I am making a difference, they understand that they can do it too! We all have important perspectives to contribute," says Sudi

In Kenya, domestic violence is common, both at home and at school. Through Erikshjälpen's LifeSkills project, school children in Kisumu are given tools to tell if they have been subjected to abuse, something they have not dared to do before. Meet Lawrence who is one of these children.

He was helped through the Lifeskills project

Talking about violence and abuse is difficult. In Kenya, the culture of silence is strong and few people dare to talk about what they have experienced. Lawrence, who goes to school in Kisumu, lives with his uncle during the semesters. In the past, his relationship with his uncle was difficult, and he was often beaten when they did not understand each other.

Last year, Lawrence and his uncle joined the LifeSkills project together. Lawrence learned to stand up for himself and his rights, and his uncle was given tools to solve problems without using violence.

- "Before, I was uncomfortable talking to my uncle, I felt shy and worried," says Lawrence. "Now I can talk about my problems and he has become better at giving me advice and support.

For a more equal, fair and sustainable Kenya

ICS-SP (Investing in children and their societies - Strengthening Families, Protecting children.) runs LifeSkills together with Erikshjälpen. In order for children to feel good, both at home and at school, they work not only with families, but also with teachers and authorities.

With the support of adults who motivate them to invest in their education and make wise life decisions, the children of Kisumu can build a better future and contribute to a more equal, just and sustainable Kenya.

Support children's right to a violence-free childhood

By supporting our work, more children like Lawrence in Kisumu can have a safe childhood. Thanks to the work of Lifeskills, we can create change and a better and safer future for children in Kenya. You can help by Give a Gift for Child Safety and Protection.

Together, we can help more children grow up in a society free from violence. Thank you for your support.